Illustrated by: Gemini 3 Nano Banana

Curious OCaml

Curious OCaml invites you to explore programming through the lens of types, logic, and algebra. OCaml is a language that rewards curiosity—its type system catches errors before your code runs, its functional style encourages clear thinking about data transformations, and its mathematical foundations reveal deep connections between programming and logic. Whether you’re new to programming, experienced with OCaml, or a seasoned developer discovering functional programming for the first time, this book aims to spark that “aha!” moment when abstract concepts click into place.

This book is intended for three audiences:

From logic rules to programming constructs

In this chapter, you will:

Conventions. OCaml code blocks are intended to be

runnable unless marked with ocaml skip (used for

illustrative or partial snippets).

Throughout this chapter we use natural deduction in the style of intuitionistic (constructive) logic. This choice is not accidental: it is exactly the fragment of logic that lines up with the “pure” core of functional programming via the Curry–Howard correspondence.

What logical connectives do you know? Before we write any code, let us take a step back and think about logic itself. The connectives listed below form the foundation of reasoning, and as we will discover, they also form the foundation of programming.

| \top | \bot | \wedge | \vee | \rightarrow |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a \wedge b | a \vee b | a \rightarrow b | ||

| truth | falsehood | conjunction | disjunction | implication |

| “trivial” | “impossible” | a and b | a or b | a gives b |

| shouldn’t get | got both | got at least one | given a, we get b |

How can we define these connectives precisely? The key insight is to think in terms of derivation trees. A derivation tree shows how we arrive at conclusions from premises, building up knowledge step by step:

\frac{ \frac{\frac{\,}{\text{a premise}} \; \frac{\,}{\text{another premise}}}{\text{some fact}} \; \frac{\frac{\,}{\text{this we have by default}}}{\text{another fact}}} {\text{final conclusion}}

We define connectives by providing rules for using them. For example, a rule \frac{a \; b}{c} matches parts of the tree that have two premises, represented by variables a and b, and have any conclusion, represented by variable c. These variables act as placeholders that can match any proposition.

Design principle: When defining a connective, we try to use only that connective in its definition. This keeps definitions self-contained and avoids circular dependencies between connectives.

Each logical connective comes with two kinds of rules:

Introduction rules tell us how to produce or construct a connective. If you want to prove “A and B”, the introduction rule tells you what you need: proofs of both A and B.

Elimination rules tell us how to use or consume a connective. If you already have “A and B”, the elimination rules tell you what you can get from it: either A or B (your choice but there is no limit on how many times you decide).

In the table below, text in parentheses provides informal commentary. Letters like a, b, and c are variables that can stand for any proposition.

| Connective | Introduction Rules | Elimination Rules |

|---|---|---|

| \top | \frac{}{\top} | doesn’t have |

| \bot | doesn’t have | \frac{\bot}{a} (i.e., anything) |

| \wedge | \frac{a \quad b}{a \wedge b} | \frac{a \wedge b}{a} (take first) \frac{a \wedge b}{b} (take second) |

| \vee | \frac{a}{a \vee b} (put first) \frac{b}{a \vee b} (put second) | \frac{a \vee b \quad \hyp{[a]^x}{c} \quad \hyp{[b]^y}{c}}{c} using x, y |

| \rightarrow | \frac{\hyp{[a]^x}{b}}{a \rightarrow b} using x | \frac{a \rightarrow b \quad a}{b} |

The notation \hyp{[a]^x}{b} (sometimes written as a tree) matches any subtree that derives b and can use a as an assumption (marked with label x), even though a might not otherwise be warranted. The square brackets around a indicate that this is a hypothetical assumption, not something we have actually established. The superscript x is a label that helps us track which assumption gets “discharged” when we complete the derivation.

This is the key to proving implications: to prove “if A then B”, we temporarily assume A and show we can derive B. For example, we can derive “sunny \rightarrow happy” by showing that assuming it is sunny, we can derive happiness:

\frac{\frac{\frac{\frac{\frac{\,}{\text{sunny}}^x}{\text{go outdoor}}}{\text{playing}}}{\text{happy}}}{\text{sunny} \rightarrow \text{happy}} \text{ using } x

Notice how the assumption “sunny” (marked with x) appears at the top of the derivation tree. We use this assumption to derive “go outdoor”, then “playing”, and finally “happy”. Once we complete the derivation, the assumption is discharged: we no longer need to assume it is sunny because we have established the conditional “sunny \rightarrow happy”.

A crucial point: such assumptions can only be used within the matched subtree! However, they can be used multiple times within that subtree. For example, if someone’s mood is more difficult to influence and requires multiple sunny conditions:

\frac{\frac{ \frac{\frac{\frac{\,}{\text{sunny}}^x}{\text{go outdoor}}}{\text{playing}} \quad \frac{\frac{\,}{\text{sunny}}^x \quad \frac{\frac{\,}{\text{sunny}}^x}{\text{go outdoor}}}{\text{nice view}} }{\text{happy}}}{\text{sunny} \rightarrow \text{happy}} \text{ using } x

In this more complex derivation, the assumption “sunny” (labeled x) is used three times: once to derive “go outdoor”, and twice more in deriving “nice view”. All three uses are valid because they occur within the same hypothetical subtree.

The elimination rule for disjunction deserves special attention because it represents reasoning by cases, one of the most fundamental proof techniques.

Suppose we know “A or B” is true, but we do not know which one. How can we still derive a conclusion C? We must show that C follows regardless of which alternative holds. In other words, we need to prove: (1) assuming A, we can derive C, and (2) assuming B, we can derive C. Since one of A or B must be true, and both lead to C, we can conclude C.

Here is a concrete example: How can we use the fact that it is sunny \vee cloudy (but not rainy)?

\frac{ \frac{\,}{\text{sunny} \vee \text{cloudy}}^{\text{forecast}} \quad \frac{\frac{\,}{\text{sunny}}^x}{\text{no-umbrella}} \quad \frac{\frac{\,}{\text{cloudy}}^y}{\text{no-umbrella}} }{\text{no-umbrella}} \text{ using } x, y

We know that it will be sunny or cloudy (by watching the weather forecast). Now we reason by cases: If it will be sunny, we will not need an umbrella. If it will be cloudy, we will not need an umbrella. Since one of these must be the case, and both lead to the same conclusion, we can confidently say: we will not need an umbrella.

We need one more kind of rule to do serious math: reasoning by induction. This rule is somewhat similar to reasoning by cases, but instead of considering a finite number of alternatives, it allows us to prove properties that hold for infinitely many cases, such as all natural numbers.

Here is the example rule for induction on natural numbers:

\frac{p(0) \quad \hyp{[p(x)]^x}{p(x+1)}}{p(n)} \text{ by induction, using } x

This rule says: we get property p for any natural number n, provided we can do two things:

Here x is a unique variable representing an arbitrary natural number. We cannot substitute a particular number for it because we write “using x” on the side, indicating that the derivation works for any choice of x.

The power of induction lies in this: once we have the base case and the inductive step, we have implicitly covered all natural numbers. Starting from p(0), we can derive p(1), then p(2), then p(3), and so on, reaching any natural number n we wish.

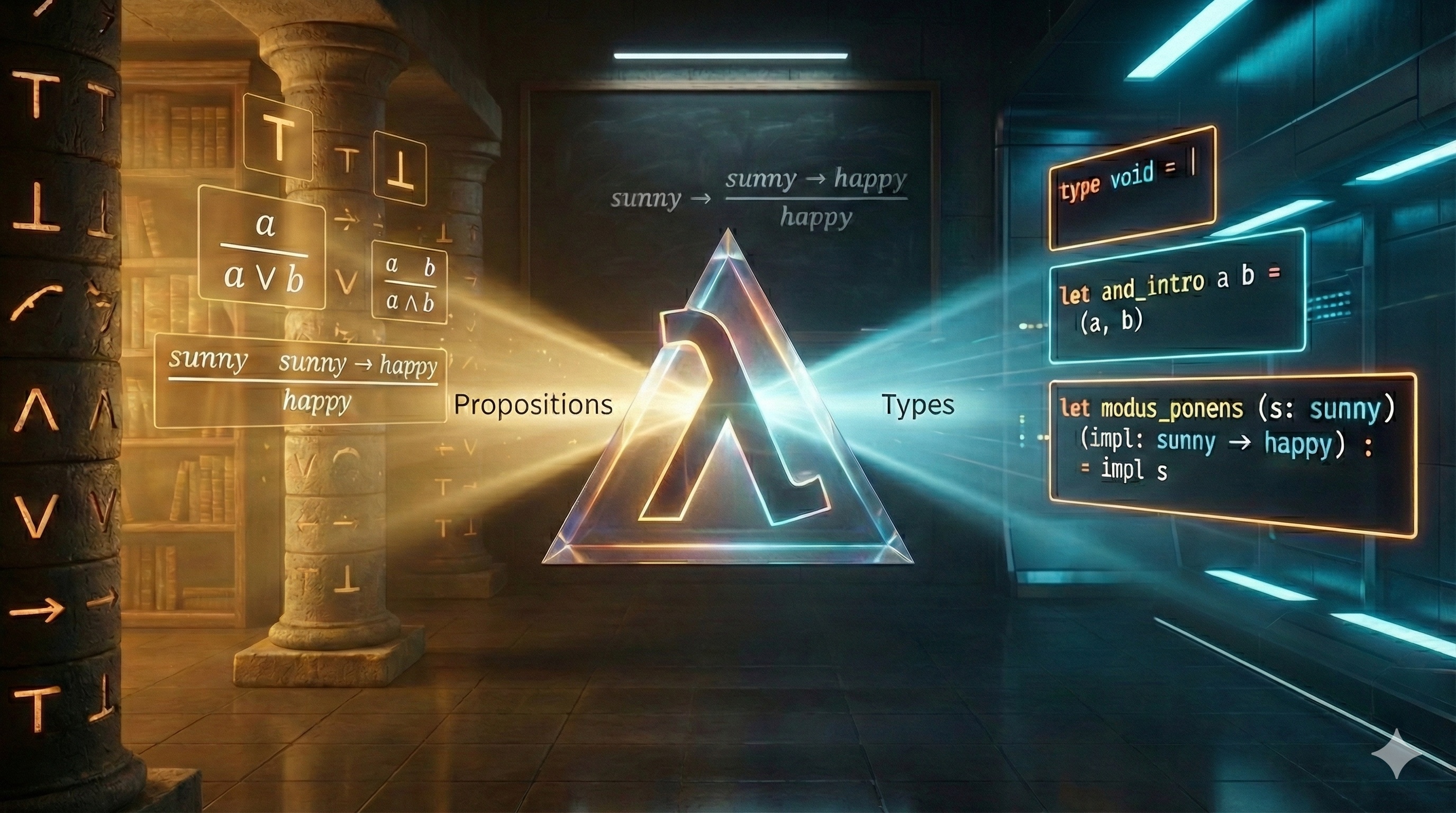

We now arrive at one of the most remarkable discoveries in the foundations of computer science: the Curry–Howard correspondence, also known as “propositions as types” or the “proofs-as-programs” interpretation. In a pure, intuitionistic setting, this correspondence is not just a metaphor: proof rules and typing rules are the same kind of object.

Under this correspondence:

When you write a well-typed program, you are (implicitly) constructing a derivation tree that proves a typing judgement.

The following table shows how each logical connective corresponds to a programming construct in OCaml:

| Logic | OCaml type (example) | Example program | Intuition |

|---|---|---|---|

| \top | unit |

() |

The trivially true proposition; the type with exactly one value |

| \bot | void (an empty type) |

match v with _ -> . |

Falsehood; a type with no values |

| \wedge | * |

(,) |

Conjunction corresponds to pairs: having both A and B |

| \vee | a variant type | Left x / Right y |

Disjunction corresponds to sums: having either A or B |

| \rightarrow | -> |

fun |

Implication corresponds to functions: given A, produce B |

| induction | - | let rec |

Inductive proofs correspond to recursive definitions |

For example, the identity function corresponds to the tautology a \rightarrow a:

# fun x -> x;;

- : 'a -> 'a = <fun>Let us now see the precise typing rules for each OCaml construct, presented in the same style as our logical rules:

Typing rules for OCaml constructs:

Unit (truth): \frac{}{\texttt{()} : \texttt{unit}}

The unit value () always has type unit.

This is like \top in logic: we can

always produce it without any premises.

Empty type (falsehood): in OCaml we can define an empty type (a type with no constructors):

type void = |There is no way to construct a value of type void using

ordinary, terminating code. But if we somehow have a

v : void, then we can derive anything from it (falsity

elimination):

let absurd (v : void) : 'a =

match v with _ -> .This corresponds closely to the logical rule \frac{\bot}{a}.

OCaml also has effects (notably exceptions). Because

raise e never returns normally, the type checker allows it

to have any result type:

\frac{e : \texttt{exn}}{\texttt{raise } e : a}

This is useful in practice, but it is also a good reminder that

effects complicate the neat “proofs-as-programs” story.

Pair (conjunction):

p : a * b we can extract either

component (e.g. by pattern matching, or via

fst/snd)To construct a pair, you need both components. To use a pair, you can extract either component. This mirrors conjunction perfectly: to prove “A and B”, you need proofs of both; given “A and B”, you can conclude either A or B.

Variant (disjunction): first, we define a sum type (a two-way choice):

type ('a, 'b) either = Left of 'a | Right of 'bx : a we get

Left x : (a, b) either, and from y : b we get

Right y : (a, b) eithert : (a, b) either and a branch for

each case, produce a result c (pattern matching)The shape of the elimination rule is exactly “reasoning by cases”: to

use an either, you must handle both Left and

Right.

let either f g = function

| Left x -> f x

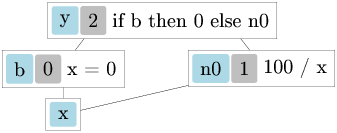

| Right y -> g yA built-in example is bool, which you can think of as a

two-constructor variant; the if ... then ... else ...

expression is just a specialized form of case analysis on a boolean.

let choose b x y =

if b then x else y

let choose' b x y =

match b with

| true -> x

| false -> yTo construct a variant, you only need one of the alternatives. To use a variant, you must handle all possible cases (pattern matching). This mirrors disjunction: to prove “A or B”, you only need one; to use “A or B”, you must consider both possibilities.

Function (implication):

To construct a function, you assume you have an input of type a (the parameter x) and show how to produce a result of type b. To use a function, you apply it to an argument. This mirrors implication: to prove “A implies B”, assume A and derive B; given “A implies B” and A, conclude B.

Recursion (induction): recursion is not a connective, but it matches the shape of induction: in a recursive definition you are allowed to assume the function being defined (the “induction hypothesis”) when defining its body.

In OCaml, recursion is introduced with let rec (there is

no standalone rec expression).

Writing out expressions and types repetitively quickly becomes tedious. More importantly, without definitions we cannot give names to our concepts, making code harder to understand and maintain. This is why we need definitions.

Type definitions are written: type ty =

some type.

In OCaml, disjunction-like types are not written as something

like a | b directly; instead, you define a variant

type and then use its constructors. For example:

type int_string_choice = A of int | B of stringThis allows us to write A x : int_string_choice for any

x : int, and B y : int_string_choice for any

y : string.

Why do we need to define variant types? The reasons are:

exhaustiveness checks, performance of generated code, and ease of type

inference. When OCaml sees A 5, it needs to figure out (or

“infer”) the type. Without a type definition, how would OCaml know

whether this is A of int | B of string or

A of int | B of float | C of bool? The definition tells

OCaml exactly what variants exist. When you match

| A i -> ..., the compiler will warn you if you forgot

to also cover C b in your match patterns.

OCaml does provide an alternative: polymorphic variants,

written with a backtick. We can write

`A x : [ `A of a | `B of b ]. With ` variants,

OCaml does infer what other variants might exist based on usage. These

types are powerful and flexible; we will discuss them in chapter

11.

Tuple elements do not need labels because we always know at which position a tuple element stands: the first element is first, the second is second, and so on. However, having labels makes code much clearer, especially when tuples have many components or components of the same type. For this reason, we can define a record type:

type int_string_record = { a : int; b : string }and create its values: {a = 7; b = "Mary"}. OCaml 5.4

and newer also support labeled tuples, we will not discuss

these.

We access the fields of records using the dot notation:

{a = 7; b = "Mary"}.b = "Mary". Unlike tuples where you

must remember “the second element is the name”, with records you can

write .b to get the field named b.

In many presentations of the Curry–Howard correspondence (and in

programming language theory), recursion is introduced via a standalone

operator often called fix. OCaml does not have a standalone

fix expression: recursion is introduced only as part of a

let rec definition.

This brings us to expression definitions, which let us give names to values. The typing rules for definitions are a bit more complex than what we have seen so far:

\frac{e_1 : a \quad \hyp{[x : a]}{e_2 : b}}{\texttt{let } x = e_1 \texttt{ in } e_2 : b}

This rule says: if e_1 has type

a, and assuming x has type a

we can show that e_2 has type b, then the whole let expression

has type b. Interestingly, this rule is

equivalent to introducing a function and immediately applying it:

let x = e1 in e2 behaves the same as

(fun x -> e2) e1. This equivalence reflects a deep

connection in the Curry–Howard correspondence.

For recursive definitions, we need an additional rule:

\frac{\hyp{[x : a]}{e_1 : a} \quad \hyp{[x : a]}{e_2 : b}}{\texttt{let rec } x = e_1 \texttt{ in } e_2 : b}

Notice the crucial difference: in the recursive case, x can appear in e_1 itself! This is what allows functions to call themselves. The name x is visible both in its own definition (e_1) and in the body that uses the definition (e_2).

These rules are slightly simplified. The full rules involve a concept called polymorphism, which we will cover in a later chapter. Polymorphism explains how the same function can work with different types.

Understanding scope—where names are visible—is essential for reading and writing OCaml programs.

Type definitions we have seen above are global: they need to be at the top-level (not nested in expressions), and they extend from the point they occur till the end of the source file or interactive session. You cannot define a type inside a function.

let-in definitions for

expressions: let x = e1 in e2 are local—the name

x is only visible within e_2. Once you exit the in part,

x no longer exists. This is useful for

temporary values that should not pollute the global namespace.

let definitions without

in are global: placing let x = e1 at the

top-level makes x visible from after

e_1 till the end of the source file or

interactive session. This is how you define functions and values that

the rest of your program can use.

In the interactive session (toplevel/REPL), we mark the end of a

top-level “sentence” with ;;. This tells OCaml “I am done

typing, please evaluate this.” In source files compiled by the build

system, ;; is unnecessary because the end of each

definition is clear from context.

Operators like +, *, <,

= are simply names of functions. In OCaml, there is nothing

magical about operators; they are ordinary functions that happen to have

special characters in their names and can be used in infix position

(between their arguments).

Just like other names, you can define your own operators:

# let (+:) a b = String.concat "" [a; b];;

val ( +: ) : string -> string -> string = <fun>

# "Alpha" +: "Beta";;

- : string = "AlphaBeta"Notice the asymmetry here: when defining an operator, we

wrap it in parentheses to tell OCaml “this is the name I am defining”.

When using the operator, we write it in the normal infix

position between its arguments. This asymmetry exists because the

definition syntax needs to distinguish between “the name

+:” and “the expression a +: b”.

An important feature of OCaml is that operators are not overloaded. This means that a single operator cannot work for multiple types. Each type needs its own set of operators:

+, *, / work for

integers+., *., /. work for floating

point numbersThis design choice makes type inference simpler and more predictable.

When you see x + y, OCaml knows immediately that

x and y must be integers.

Exception: The comparison operators

<, =, <=,

>=, <> do work for all values other

than functions. These are called polymorphic comparisons.

The following exercises are adapted from Think OCaml: How to Think Like a Computer Scientist by Nicholas Monje and Allen Downey. They will help you get comfortable with OCaml’s syntax and type system.

Assume that we execute the following assignment statements:

let width = 17

let height = 12.0

let delimiter = '.'For each of the following expressions, write the value of the expression and the type (of the value of the expression), or the resulting type error.

width/2width/.2.0height/31 + 2 * 5delimiter * 5Practice using the OCaml interpreter as a calculator:

You’ve probably heard of the Fibonacci numbers before, but in case you haven’t, they’re defined by the following recursive relationship:

\begin{cases} f(0) = 0 \\ f(1) = 1 \\ f(n+1) = f(n) + f(n-1) & \text{for } n = 2, 3, \ldots \end{cases}

Write a recursive function to calculate these numbers.

A palindrome is a word that is spelled the same backward and forward, like “noon” and “redivider”. Recursively, a word is a palindrome if the first and last letters are the same and the middle is a palindrome.

The following are functions that take a string argument and return the first, last, and middle letters:

let first_char word = word.[0]

let last_char word =

let len = String.length word - 1 in

word.[len]

let middle word =

let len = String.length word - 2 in

String.sub word 1 lenmiddle with a string with two letters?

One letter? What about the empty string ""?is_palindrome that takes a

string argument and returns true if it is a palindrome and

false otherwise.The greatest common divisor (GCD) of a and b is the largest number that divides both of them with no remainder.

One way to find the GCD of two numbers is Euclid’s algorithm, which is based on the observation that if r is the remainder when a is divided by b, then \gcd(a, b) = \gcd(b, r). As a base case, we can consider \gcd(a, 0) = a.

Write a function called gcd that takes parameters

a and b and returns their greatest common

divisor.

If you need help, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Euclidean_algorithm.

Algebraic data types and some curious analogies

In this chapter, we will deepen our understanding of OCaml’s type system by working through type inference examples by hand. Then we will explore algebraic data types—a cornerstone of functional programming that allows us to define rich, structured data. Along the way, we will discover a surprising and beautiful connection between these types and ordinary polynomials from high-school algebra.

In this chapter, you will:

For a refresher, let us apply the type inference rules introduced in

Chapter 1 to some simple examples. We will start with the identity

function fun x -> x—perhaps the simplest possible

function, yet one that reveals important aspects of polymorphism. In the

derivations below, [?] means “unknown

(to be inferred)”.

We begin with an incomplete derivation:

\frac{[?]}{\texttt{fun x -> x} : [?]}

Using the \rightarrow introduction

rule, we need to derive the body x assuming x

has some type a:

\frac{\hyp{[x : a]^x}{\texttt{x} : a}}{\texttt{fun x -> x} : [?] \rightarrow [?]}

The premise is a hypothetical derivation: inside the body we are

allowed to use the assumption x : a. Since the body is just

x, the result type is also a, and we conclude:

\frac{\hyp{[x : a]^x}{\texttt{x} : a}}{\texttt{fun x -> x} : a \rightarrow a}

Because a is arbitrary (we made no

assumptions constraining it), OCaml introduces a type variable

'a to represent it. This is how polymorphism emerges

naturally from the inference process—the identity function can work with

values of any type:

# fun x -> x;;

- : 'a -> 'a = <fun>Now let us try something that will constrain the types more:

fun x -> x+1. This is the same as

fun x -> ((+) x) 1 (try it in OCaml to verify!). The

addition operator forces specific types upon us.

We will use the notation [?\alpha] to mean “type unknown yet, but the same as in other places marked [?\alpha].” This notation helps us track how constraints propagate through the derivation.

Starting the derivation and applying \rightarrow introduction:

\frac{\frac{[?]}{\texttt{((+) x) 1} : [?\alpha]}}{\texttt{fun x -> ((+) x) 1} : [?] \rightarrow [?\alpha]}

Applying \rightarrow elimination

(function application) to ((+) x) 1:

\frac{\frac{\frac{[?]}{\texttt{(+) x} : [?\beta] \rightarrow [?\alpha]} \quad \frac{[?]}{\texttt{1} : [?\beta]}}{\texttt{((+) x) 1} : [?\alpha]}}{\texttt{fun x -> ((+) x) 1} : [?] \rightarrow [?\alpha]}

We know that 1 : int, so [?\beta] = \texttt{int}:

\frac{\frac{\frac{[?]}{\texttt{(+) x} : \texttt{int} \rightarrow [?\alpha]} \quad \frac{\,}{\texttt{1} : \texttt{int}}^{\text{(constant)}}}{\texttt{((+) x) 1} : [?\alpha]}}{\texttt{fun x -> ((+) x) 1} : [?] \rightarrow [?\alpha]}

Applying function application again to (+) x:

\frac{\frac{\frac{\frac{[?]}{\texttt{(+)} : [?\gamma] \rightarrow \texttt{int} \rightarrow [?\alpha]} \quad \frac{[?]}{\texttt{x} : [?\gamma]}}{\texttt{(+) x} : \texttt{int} \rightarrow [?\alpha]} \quad \frac{\,}{\texttt{1} : \texttt{int}}^{\text{(constant)}}}{\texttt{((+) x) 1} : [?\alpha]}}{\texttt{fun x -> ((+) x) 1} : [?\gamma] \rightarrow [?\alpha]}

Since (+) : int -> int -> int, we have [?\gamma] = \texttt{int} and [?\alpha] = \texttt{int}:

\frac{\frac{\frac{\frac{\,}{\texttt{(+)} : \texttt{int} \rightarrow \texttt{int} \rightarrow \texttt{int}}^{\text{(constant)}} \quad \frac{\,}{\texttt{x} : \texttt{int}}^x}{\texttt{(+) x} : \texttt{int} \rightarrow \texttt{int}} \quad \frac{\,}{\texttt{1} : \texttt{int}}^{\text{(constant)}}}{\texttt{((+) x) 1} : \texttt{int}}}{\texttt{fun x -> ((+) x) 1} : \texttt{int} \rightarrow \texttt{int}}

When there are several arrows “on the same depth” in a function type,

it means that the function returns a function. For example,

(+) : int -> int -> int is just a shorthand for

(+) : int -> (int -> int). The arrow associates to

the right, so we can omit the parentheses.

This is very different from:

\texttt{fun f -> (f 1) + 1} : (\texttt{int} \rightarrow \texttt{int}) \rightarrow \texttt{int}

In the first case, (+) is a function that takes an

integer and returns a function from integers to integers. In the second

case, we have a function that takes a function as an argument—a

higher-order function. The parentheses around

int -> int are essential here; without them, the meaning

would be completely different.

This style of defining multi-argument functions, where each function takes one argument and returns another function expecting the remaining arguments, is called curried form (named after logician Haskell Curry). It enables a powerful technique called partial application.

For example, instead of writing (fun x -> x+1), we

can simply write ((+) 1). Here we apply (+) to

just one argument, getting back a function that adds 1 to its input.

What expanded form does ((+) 1) correspond to exactly

(computationally)?

Think about it before reading on…

It corresponds to fun y -> 1 + y. We have “baked in”

the first argument, and the resulting function waits for the second.

We will become more familiar with functions returning functions when we study the lambda calculus in a later chapter.

In Chapter 1, we learned about the unit type and variant

types like:

type int_string_choice = A of int | B of stringWe also covered tuple types, record types, and type definitions. Now let us explore these concepts more deeply, building up to the powerful notion of algebraic data types.

Variants do not have to carry arguments. Instead of writing

A of unit, we can simply use A. This is more

convenient and idiomatic:

type color = Red | Green | BlueThis defines a type with exactly three possible values—no more, no less. The compiler knows this, which enables exhaustive pattern matching checks.

A subtle point about OCaml: In OCaml, variants take

multiple arguments rather than taking tuples as arguments. This means

A of int * string is different from

A of (int * string). The first takes two separate

arguments, while the second takes a single tuple argument. This

distinction is usually not important—until you get bitten by it in some

corner case! For most purposes, you can ignore it.

Here is where things get really interesting: type definitions can be recursive! This allows us to define data structures of arbitrary size using a finite definition:

type int_list = Empty | Cons of int * int_listLet us see what values inhabit int_list. The definition

tells us there are two ways to build an int_list:

Empty represents the empty list—a list with no

elementsCons (5, Empty) is a list containing just 5Cons (5, Cons (7, Cons (13, Empty))) is a list

containing 5, 7, and 13.Notice how Cons takes an integer and another

int_list, allowing us to chain together as many elements as

we like. This recursive structure is the essence of how functional

languages represent unbounded data.

The built-in type bool really does behave like a

two-constructor variant with values true and

false—but note a small OCaml wrinkle: user-defined

constructors must start with a capital letter, while a few built-in

constructors like true, false,

[], and (::) are special-cased.

Similarly, int can be thought of as a very

large finite variant (“one constructor per integer”), even though the

compiler implements it as an efficient machine integer rather than as a

gigantic sum type.

Our int_list type only works with integers. But what if

we want a list of strings? Or a list of booleans? We would have to

define separate types for each, duplicating the same structure.

Type definitions can be parametric with respect to the types of their components. This allows us to define generic data structures that work with any element type. OCaml already has a built-in parametric list type, so to avoid shadowing it we will define our own simplified list type:

type 'a my_list = Empty | Cons of 'a * 'a my_listThe 'a is a type parameter—a placeholder that

gets filled in when we use the type. We can have a

string my_list, an int my_list, or even an

(int my_list) my_list (a list of lists of integers).

Several conventions and syntax rules apply to parametric types:

Type variables must start with '. When printing

inferred types, OCaml may rename these variables, so it is customary to

stick to the standard names 'a, 'b,

'c, 'd, etc.

The OCaml syntax places the type parameter before the type name, mimicking English word order. A silly example that reads almost like English:

type 'white_color dog = Dog of 'white_colorThis defines a “white-color dog” type—the syntax reads naturally!

With multiple parameters, OCaml uses parentheses:

type ('a, 'b) choice = Left of 'a | Right of 'bCompare this to F# syntax:

type choice<'a,'b> = Left of 'a | Right of 'b

And Haskell syntax:

data Choice a b = Left a | Right b

Different languages have different conventions, but the underlying concept is the same.

OCaml provides various syntactic conveniences—sometimes called syntactic sugar—that make code more pleasant to write and read. Let us survey the most important ones.

Names of variants, called constructors, must start with a capital letter. If we wanted to define our own booleans, we would write:

type my_bool = True | FalseOnly constructors and module names can start with capital letters in OCaml. Everything else (values, functions, type names) must start with a lowercase letter. This convention makes it easy to distinguish constructors at a glance.

(As noted above, a few built-in constructors like true,

false, [], and (::) are special

exceptions to the capitalization rule.)

Modules are organizational units (like “shelves”) containing

related values. For example, the List module provides

operations on lists, including List.map and

List.filter. We will learn more about modules in later

chapters.

Did we mention that we can use dot notation to access record fields?

The syntax record.field extracts a field value. For

example, if we have let person = {name="Alice"; age=30}, we

can write person.name to get "Alice".

Several syntactic shortcuts make function definitions more concise. These are worth memorizing, as you will see them constantly in OCaml code:

fun x y -> e stands for

fun x -> fun y -> e. Note that

fun x -> fun y -> e parses as

fun x -> (fun y -> e). This shorthand aligns with

curried form—we can write multi-argument functions without nesting

fun expressions.

function A x -> e1 | B y -> e2 stands for

fun p -> match p with A x -> e1 | B y -> e2. The

general form is: function PATTERN-MATCHING stands for

fun v -> match v with PATTERN-MATCHING. This is handy

when you want to immediately pattern-match on a function’s

argument.

let f ARGS = e is a shorthand for

let f = fun ARGS -> e. This is probably the most common

way to define functions in practice.

Pattern matching is one of the most powerful features of OCaml and similar languages. It lets us examine the structure of data and extract components in a single, elegant construct.

Recall that we introduced fst and snd as

means to access elements of a pair. But what about larger tuples? There

is no built-in thd for the third element. The fundamental

way to access any tuple—or any algebraic data type—uses the

match construct. In fact, fst and

snd can easily be defined using pattern matching:

let fst p = match p with (a, b) -> a

let snd p = match p with (a, b) -> bThe pattern (a, b) destructures the pair,

binding its first component to a and its second to

b. We then return whichever component we want.

Pattern matching also works with records, letting us extract multiple fields at once:

type person = { name : string; surname : string; age : int }

let greet_person () =

match { name = "Walker"; surname = "Johnnie"; age = 207 } with

| { name = _; surname = sn; age = _ } -> "Hi " ^ sn ^ "!"Here we match against a record pattern. Note that we use wildcards

_ for name and age (ignoring

them), while binding surname to sn—then use

sn in the greeting.

The left-hand sides of -> in match

expressions are called patterns. Patterns describe the

structure of values we want to match against. They can include:

1, "hello", or

true)None, Some x, or

Cons (h, t))Patterns can be nested to arbitrary depth, allowing us to match complex structures in one go:

match Some (5, 7) with

| None -> "sum: nothing"

| Some (x, y) -> "sum: " ^ string_of_int (x + y)Here Some (x, y) is a nested pattern: we match

Some of something, and that something must be a

pair, whose components we bind to x and y.

A pattern can simply bind the entire value without destructuring.

Writing match f x with v -> ... is the same as

let v = f x in .... This is occasionally useful when you

want the syntax of match but do not need to take the value

apart.

When we do not need a value in a pattern, it is good practice to use

the underscore _, which is a wildcard. The

wildcard matches anything but does not bind it to a name. This signals

to the reader (and the compiler) that we are intentionally ignoring that

part:

let fst (a, _) = a

let snd (_, b) = bUsing _ instead of an unused variable name avoids

compiler warnings about unused bindings.

A variable can only appear once in a pattern. This property is called

linearity. You might think this is a limitation—what if we want

to check that two parts of a structure are equal? We cannot write

(x, x) to match pairs with equal components.

However, we can add conditions to patterns using when,

so linearity is not really a limitation in practice:

let describe_point p =

match p with

| (x, y) when x = y -> "diag"

| _ -> "off-diag"The when clause acts as a guard: the pattern matches

only if both the structure matches and the condition is

true.

Here is a more elaborate example showing how to implement a

comparison function (without shadowing the standard

compare):

let compare_int a b =

match a, b with

| (x, y) when x < y -> -1

| (x, y) when x = y -> 0

| _ -> 1Notice how we match against the tuple (a, b) in

different ways, using guards to distinguish the cases.

We can skip unused fields of a record in a pattern. Only the fields we care about need to be mentioned. This keeps patterns concise and means we do not have to update every pattern when we add a new field to a record type.

We can compress patterns by using | inside a single

pattern to match multiple alternatives. This is different from having

multiple pattern clauses—it lets us share a single right-hand side for

several patterns:

type month =

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun

| Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec

type weekday = Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat | Sun

type calendar_date =

{ year : int; month : month; day : int; weekday : weekday }

let day =

{ year = 2012; month = Feb; day = 14; weekday = Wed }

let day_kind =

match day with

| { weekday = Sat | Sun; _ } -> "Weekend!"

| _ -> "Work day"The pattern Sat | Sun matches either Sat or

Sun. This is much cleaner than writing two separate clauses

with the same right-hand side.

asSometimes we want to both destructure a value and keep a

reference to the whole thing (or some intermediate part). We use

(pattern as v) to name a nested pattern, binding the

matched value to v:

match day with

| {weekday = (Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri as wday); _}

when not (day.month = Dec && day.day = 24) ->

Some (work (get_plan wday))

| _ -> NoneThis example demonstrates several features working together:

as wday clause binds the matched weekday to the

variable wdaywhen guard checks that it is not Christmas Evewday is then used in the expression

get_plan wdayThis combination of features makes OCaml’s pattern matching remarkably expressive.

Now we come to one of the most delightful aspects of algebraic data types: they really are algebraic in a precise mathematical sense. Let us explore a curious analogy between types and polynomials that turns out to be surprisingly deep.

The translation from types to mathematical expressions works as follows:

| (variant choice) with + (addition)* (tuple product) with \times (multiplication); as \times)We also need translations for some special types:

The void type (a type with no constructors, hence no values):

type void = |Since no values can be constructed, it represents emptiness—translate it as 0.

The unit type has exactly one value, so

translate it as 1. Since variants

without arguments behave like variants of unit, translate

them as 1 as well.

The bool type has exactly two values

(true and false), so translate it as 2.

Types like int, string,

float, and type parameters are treated as variables. We do

not care about their exact number of values; we just give them symbolic

names like x, y, etc.

Defined types translate according to their definitions (substituting variables as necessary).

Give a name to the type being defined (representing a function of the introduced variables). Now interpret the result as an ordinary numeric polynomial! (Or a “rational function” if recursively defined.)

This might seem like a mere curiosity, but it leads to real insights. Let us have some fun with it!

type ymd = { year : int; month : int; day : int }A simple “year-month-day” record is a product of three

int fields. Translating to a polynomial (using x for int):

D = x \times x \times x = x^3

The cube makes sense: this record is essentially a triple of integers.

The built-in option type is defined as:

type 'a option = None | Some of 'aTranslating (using x for the type

parameter 'a):

O = 1 + x

This reads as: an option is either nothing (1) or something of type x. The polynomial 1 + x is beautifully simple!

type 'a my_list = Empty | Cons of 'a * 'a my_listTranslating (where L represents the list type itself, and x represents the element type):

L = 1 + x \cdot L

This is a recursive equation! A list is either empty (1) or an element times another list (x \cdot L). If you solve this equation algebraically, you get L = \frac{1}{1-x} = 1 + x + x^2 + x^3 + \ldots, which corresponds to: a list is either empty, or has one element, or has two elements, etc.

type btree = Tip | Node of int * btree * btreeTranslating:

T = 1 + x \cdot T \cdot T = 1 + x \cdot T^2

A binary tree is either a tip (1) or a node containing a value and two subtrees (x \cdot T^2).

Here is the remarkable payoff: when translations of two types are equal according to the laws of high-school algebra, the types are isomorphic. This means there exist bijective (one-to-one and onto) functions between them—you can convert from one type to the other and back without losing any information.

Let us play with the binary tree polynomial and see where algebra takes us:

\begin{aligned} T &= 1 + x \cdot T^2 \\ &= 1 + x \cdot T + x^2 \cdot T^3 \\ &= 1 + x + x^2 \cdot T^2 + x^2 \cdot T^3 \\ &= 1 + x + x^2 \cdot T^2 \cdot (1 + T) \\ &= 1 + x \cdot (1 + x \cdot T^2 \cdot (1 + T)) \end{aligned}

Each step uses standard algebraic manipulations: substituting T = 1 + xT^2, expanding, factoring, and rearranging. The result is a different but algebraically equivalent expression.

Now let us translate this resulting expression back to a type:

type repr =

(int * (int * btree * btree * btree option) option) optionReading the polynomial 1 + x \cdot (1 + x

\cdot T^2 \cdot (1 + T)) from outside in: we have an option (the

outermost 1 + \ldots), whose

Some case contains an int times another

option, and so on.

The challenge is to find isomorphism functions with signatures:

val iso1 : btree -> repr

val iso2 : repr -> btreeThese functions should satisfy: for all trees t,

iso2 (iso1 t) = t, and for all representations

r, iso1 (iso2 r) = r. Can you write them?

Here is my first attempt, trying to guess the pattern directly:

# let iso1 (t : btree) : repr =

match t with

| Tip -> None

| Node (x, Tip, Tip) -> Some (x, None)

| Node (x, Node (y, t1, t2), Tip) ->

Some (x, Some (y, t1, t2, None))

| Node (x, Node (y, t1, t2), t3) ->

Some (x, Some (y, t1, t2, Some t3));;

Warning 8: this pattern-matching is not exhaustive.

Here is an example of a value that is not matched:

Node (_, Tip, Node (_, _, _))I forgot about one case! The case

Node (_, Tip, Node (_, _, _))—a node with an empty left

subtree and non-empty right subtree—was not covered. It seems difficult

to guess the solution directly when trying to map the complex final form

all at once.

Have you found it on your first try? If so, congratulations! Most people do not. This illustrates an important principle: complex transformations are easier to get right when broken into smaller steps.

Let us divide the task into smaller steps corresponding to intermediate points in the polynomial transformation. Instead of jumping from T = 1 + xT^2 directly to the final form, we will introduce intermediate types for each algebraic step:

type ('a, 'b) choice = Left of 'a | Right of 'b

type interm1 =

((int * btree, int * int * btree * btree * btree) choice)

option

type interm2 =

((int, int * int * btree * btree * btree option) choice)

optionNow we can define each step:

let step1r (t : btree) : interm1 =

match t with

| Tip -> None

| Node (x, t1, Tip) -> Some (Left (x, t1))

| Node (x, t1, Node (y, t2, t3)) ->

Some (Right (x, y, t1, t2, t3))

let step2r (r : interm1) : interm2 =

match r with

| None -> None

| Some (Left (x, Tip)) -> Some (Left x)

| Some (Left (x, Node (y, t1, t2))) ->

Some (Right (x, y, t1, t2, None))

| Some (Right (x, y, t1, t2, t3)) ->

Some (Right (x, y, t1, t2, Some t3))

let step3r (r : interm2) : repr =

match r with

| None -> None

| Some (Left x) -> Some (x, None)

| Some (Right (x, y, t1, t2, t3opt)) ->

Some (x, Some (y, t1, t2, t3opt))

let iso1 (t : btree) : repr =

step3r (step2r (step1r t))Each step function handles one small transformation, and the compiler verifies that our pattern matching is exhaustive. No more missed cases!

Define step1l, step2l, step3l,

and iso2.

Hint: Now it is straightforward—each step is simply the inverse of its corresponding forward step. The left-going functions undo what the right-going functions do.

This exploration of type isomorphisms teaches us two valuable principles:

Design for validity: Try to define data structures so that only meaningful information can be represented—as long as it does not overcomplicate the data structures. Avoid catch-all clauses when defining functions. The compiler will then tell you if you have forgotten about a case. The exhaustiveness checker is your friend.

Divide and conquer: Break solutions into small

steps so that each step can be easily understood and verified. When I

tried to write iso1 directly, I made a mistake. When I

broke it into three simple steps, each step was obviously correct, and

composing them gave the right answer.

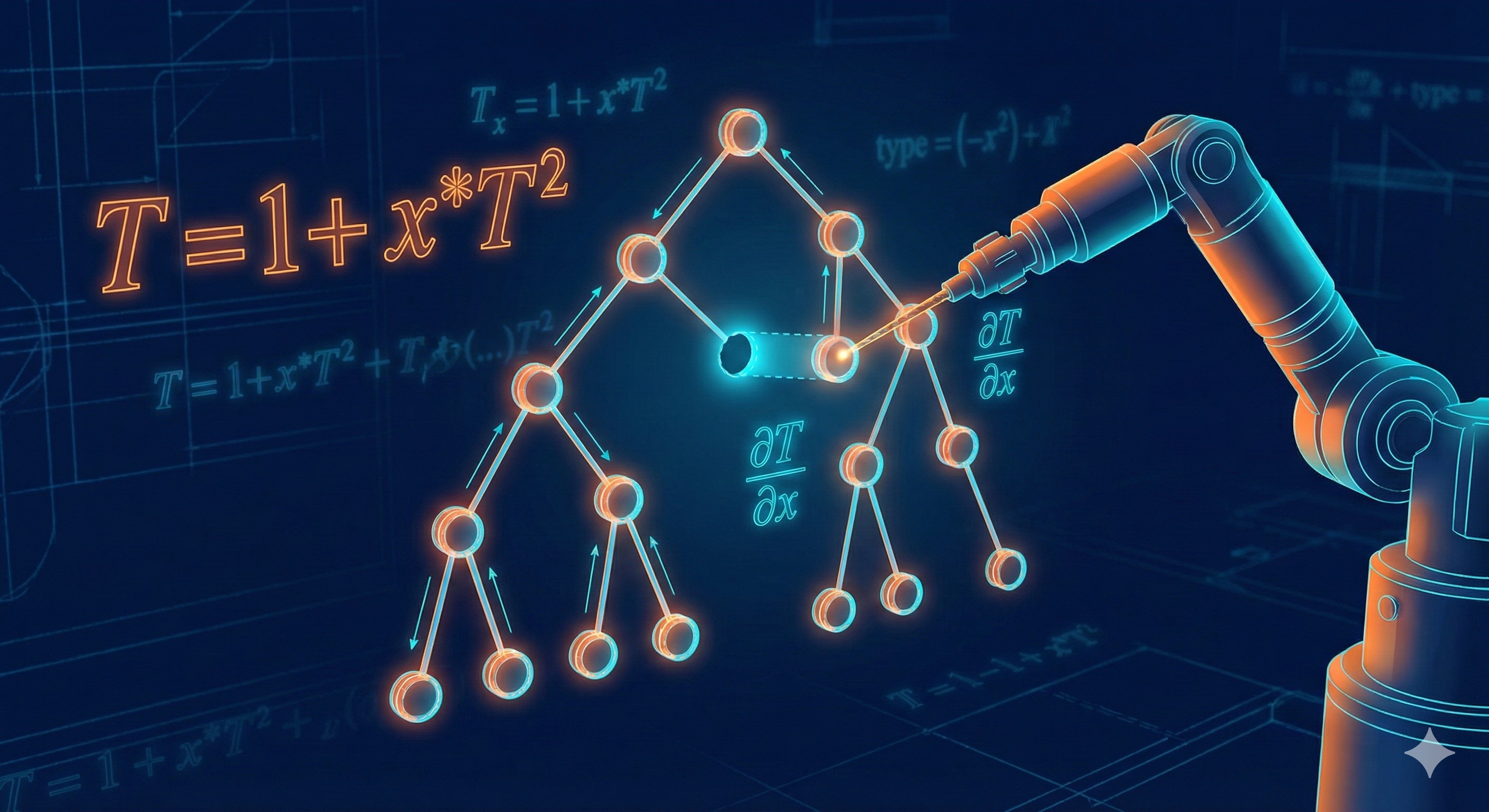

Of course, you might object that the pompous title is wrong—we will differentiate the translated polynomials, not the types themselves. Fair enough! But what sense does differentiating a type’s polynomial make?

It turns out that taking the partial derivative of a polynomial (translated from a data type), when translated back, gives a type representing a “one-hole context”—a data structure with one piece missing. This missing piece corresponds to the variable with respect to which we differentiated. The derivative tells us: “Here are all the ways to point at one element of this type.”

Let us start with a simple record type:

type ymd = { year : int; month : int; day : int }The translation and its derivative:

\begin{aligned} D &= x \cdot x \cdot x = x^3 \\ \frac{\partial D}{\partial x} &= 3x^2 = x \cdot x + x \cdot x + x \cdot x \end{aligned}

We could have left it as 3 \cdot x \cdot

x, but expanding it as a sum shows the structure more clearly.

The derivative 3x^2 says: there are

three ways to “point at” an int in a ymd, and

each way leaves two other ints behind.

Translating the expanded form back to a type:

type ymd_ctx =

Year of int * int | Month of int * int | Day of int * intEach variant represents a “hole” at a different position:

Year (m, d) means the year field is the hole (and we

have the month m and day d)Month (y, d) means the month field is the hole (and we

have year y and day d)Day (y, m) means the day field is the hole.Now we can define functions to introduce and eliminate this derivative type:

let ymd_deriv ({ year = y; month = m; day = d } : ymd) =

[ Year (m, d); Month (y, d); Day (y, m) ]

let ymd_integr n = function

| Year (m, d) -> { year = n; month = m; day = d }

| Month (y, d) -> { year = y; month = n; day = d }

| Day (y, m) -> { year = y; month = m; day = n }

let example =

List.map (ymd_integr 7) (ymd_deriv { year = 2012; month = 2; day = 14 })The ymd_deriv function produces all contexts (one for

each field)—it “differentiates” a record into a list of one-hole

contexts. The ymd_integr function fills in a hole with a

new value—it “integrates” by putting a value back into the context.

Notice how the naming follows the calculus analogy!

The example above takes the date February 14, 2012, produces three contexts (one for each field), and then fills each hole with the number 7, producing three modified dates.

Now let us tackle the more challenging case of binary trees (using

the same btree type as above):

type btree = Tip | Node of int * btree * btreeThe translation and differentiation:

\begin{aligned} T &= 1 + x \cdot T^2 \\ \frac{\partial T}{\partial x} &= 0 + T^2 + 2 \cdot x \cdot T \cdot \frac{\partial T}{\partial x} = T \cdot T + 2 \cdot x \cdot T \cdot \frac{\partial T}{\partial x} \end{aligned}

Something interesting happened: the derivative is recursive! It refers to itself via \frac{\partial T}{\partial x}. This makes perfect sense when you think about it:

Instead of translating 2 as

bool, we introduce a more descriptive type to make the code

clearer:

type btree_dir = LeftBranch | RightBranch

type btree_deriv =

| Here of btree * btree

| Below of btree_dir * int * btree * btree_derivThe Here constructor means the hole is at the current

position, and we have the left and right subtrees. The

Below constructor means we go down one level, remembering

which direction we went, the value at the node we passed, and the

subtree we did not enter.

(You might someday hear about zippers—they are “inverted” relative to our type. In a zipper, the hole comes first, and the context trails behind. Both representations are useful in different situations.)

Write a function that takes a number and a btree_deriv,

and builds a btree by putting the number into the “hole” in

btree_deriv.

The integration function fills the hole with a value. It must be

recursive because the derivative type is recursive—we may need to

descend through multiple Below constructors before reaching

the Here where the hole actually is:

let rec btree_integr n = function

| Here (ltree, rtree) -> Node (n, ltree, rtree)

| Below (LeftBranch, m, rtree, deriv) ->

Node (m, btree_integr n deriv, rtree)

| Below (RightBranch, m, ltree, deriv) ->

Node (m, ltree, btree_integr n deriv)When we reach Here, we create a node with the new value

n and the two subtrees. When we see Below, we

reconstruct the node we passed through and recursively integrate into

the appropriate subtree.

Due to Yaron Minsky.

This exercise practices the principle of “making invalid states

unrepresentable.” Consider a datatype to store internet connection

information. The time when_initiated marks the start of

connecting and is not needed after the connection is established (it is

only used to decide whether to give up trying to connect). The ping

information is available for established connections but not straight

away.

type connectionstate = Connecting | Connected | Disconnected

type connectioninfo = {

state : connectionstate;

server : Inetaddr.t;

lastpingtime : Time.t option;

lastpingid : int option;

sessionid : string option;

wheninitiated : Time.t option;

whendisconnected : Time.t option;

}(The types Time.t and Inetaddr.t come from

the Core library. You can replace them with float

and Unix.inet_addr. Load the Unix library in the

interactive toplevel with #load "unix.cma";;.)

The problem with this design is that it allows many nonsensical

combinations: a Connecting state with ping information, a

Disconnected state with a session ID, etc. The optional

fields (all those option types) make it unclear which

fields are valid in which states.

Rewrite the type definitions so that the datatype will contain only reasonable combinations of information. Use separate record types for each connection state, with only the fields that make sense for that state.

In OCaml, functions can have labeled arguments and optional arguments (parameters with default values that can be omitted). This exercise explores these features.

Labels can differ from the names of argument values:

let f ~meaningfulname:n = n + 1

let _ = f ~meaningfulname:5 (* We do not need the result so we ignore it. *)When the label and value names are the same, the syntax is shorter:

let g ~pos ~len =

StringLabels.sub "0123456789abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz" ~pos ~len

let () = (* A nicer way to mark computations that return unit. *)

let pos = Random.int 26 in

let len = Random.int 10 in

print_string (g ~pos ~len)When some function arguments are optional, the function must take non-optional arguments after the last optional argument. Optional parameters with default values:

let h ?(len=1) pos = g ~pos ~len

let () = print_string (h 10)Optional arguments are implemented as parameters of an option type. This allows checking whether the argument was provided:

let foo ?bar n =

match bar with

| None -> "Argument = " ^ string_of_int n

| Some m -> "Sum = " ^ string_of_int (m + n)We can use it in various ways:

let _ = foo 5

let _ = foo ~bar:5 7We can also provide the option value directly:

let test_foo () =

let bar = if Random.int 10 < 5 then None else Some 7 in

foo ?bar 7Observe the types that functions with labeled and optional arguments have. Come up with coding style guidelines for when to use labeled arguments. When might they improve readability? When might they be overkill?

Write a rectangle-drawing procedure that takes three optional arguments: left-upper corner, right-lower corner, and a width-height pair. It should draw a correct rectangle whenever two of the three arguments are given (since any two determine the third), and raise an exception otherwise. Use the Bogue library.

Write a function that takes an optional argument of arbitrary type and a function argument, and passes the optional argument to the function without inspecting it. This tests your understanding of how optional arguments work at the type level.

From a past exam.

These exercises help you internalize how type inference works. Try to work them out by hand before checking with the OCaml toplevel.

let double f y = f (f y) in fun g x -> double (g x)let rec tails l = match l with [] -> [] | x::xs -> xs::tails xs in fun l -> List.combine l (tails l)(int -> int) -> bool'a option -> 'a listWe have seen that algebraic data types can be related to analytic functions (the subset definable from polynomials via recursion)—by literally interpreting sum types (variant types) as sums and product types (tuple and record types) as products. We can extend this interpretation to function types by interpreting a \rightarrow b as b^a (i.e., b to the power of a). Note that the b^a notation is actually used to denote functions in set theory.

This interpretation makes sense: a function from a set with a elements to a set with b elements is choosing, for each of the a inputs, one of b outputs—giving b^a possible functions.

Translate a^{b + cd} and a^b \cdot (a^c)^d into OCaml types, using any

distinct types for a, b, c, d, and

using type ('a,'b) choice = Left of 'a | Right of 'b for

+. Write the bijection functions in

both directions. Verify algebraically that a^{b + cd} = a^b \cdot (a^c)^d using the laws

of exponents.

Come up with a type 't exp that shares with the

exponential function the following property: \frac{\partial \exp(t)}{\partial t} =

\exp(t), where we translate a derivative of a type as a context

(i.e., the type with a “hole”), as in this chapter. In other words, the

derivative of the type should be isomorphic to the type itself! Explain

why your answer is correct. Hint: in computer science, our

logarithms are mostly base 2.

Further reading: Algebraic Type Systems - Combinatorial Species

Write a function btree_deriv_at that takes a predicate

over integers (i.e., a function f: int -> bool) and a

btree, and builds a btree_deriv whose “hole”

is in the first position for which the predicate returns true. It should

return a btree_deriv option, with None if the

predicate does not hold for any node.

This function lets you “search” a tree and get back a context pointing to the found element. Think about what order you want to search in (pre-order, in-order, or post-order) and what “first” means in that context.

Reduction semantics and operational reasoning

In this chapter, you will:

References:

In this chapter, we explore how functional programs actually execute. We will learn how to reason about computation step by step using reduction semantics, and discover important optimization techniques like tail call optimization that make functional programming practical. Along the way, we will encounter our first taste of continuation passing style, a powerful programming technique that will reappear throughout this book.

Function composition is one of the most fundamental operations in functional programming. It allows us to build complex transformations by combining simpler functions. The usual way function composition is defined in mathematics is “backward”—the notation follows the convention of mathematical function application:

(f \circ g)(x) = f(g(x))

This means that when we write f \circ g, we first apply g and then apply f to the result. The function written on the left is applied last—hence the term “backward” composition. Here is how this is expressed in different functional programming languages:

| Language | Definition |

|---|---|

| Math | (f \circ g)(x) = f(g(x)) |

| OCaml | let (-|) f g x = f (g x) |

| F# | let (<<) f g x = f (g x) |

| Haskell | (.) f g = \x -> f (g x) |

This backward composition looks like function application but needs

fewer parentheses. Do you recall the functions iso1 and

iso2 from the previous chapter on type isomorphisms? Using

backward composition, we could write:

let iso2 = step1l -| step2l -| step3lWhile backward composition matches traditional mathematical notation, many programmers find a “forward” composition more intuitive. Forward composition follows the order in which computation actually proceeds—data flows from left to right, matching how we typically read code in most programming languages:

| Language | Definition |

|---|---|

| OCaml | let (\|-) f g x = g (f x) |

| F# | let (>>) f g x = g (f x) |

With forward composition, you can read a pipeline of transformations in the natural order:

let iso1 = step1r |- step2r |- step3rHere, the data first passes through step1r, then the

result goes to step2r, and finally to step3r.

This “pipeline” style of programming is particularly popular in

languages like F# and has influenced the design of many modern

programming languages.

In the table above, the operator is written as \|-

because Markdown tables use | to separate columns. In

actual OCaml code, the operator name is (|-).

let (|-) f g x = g (f x)Two related (but distinct) tools are also worth knowing:

Fun.compose, where

Fun.compose f g x = f (g x).(|>) (a pipeline): x |> f |> g means

g (f x). Unlike (|-), this is not composition

of functions but immediate application to a value.Both composition examples above rely on partial

application, a technique we introduced in the previous chapter.

Recall that ((+) 1) is a function that adds 1 to its

argument—we have provided only one of the two arguments that

(+) requires. Partial application occurs whenever we supply

fewer arguments than a function expects; the result is a new function

that waits for the remaining arguments.

Consider the composition step1r |- step2r |- step3r. How

exactly does partial application come into play here? The composition

operator (|-) is defined as

let (|-) f g x = g (f x), which means it takes

three arguments: two functions f and

g, and a value x. When we write

step1r |- step2r, we are partially applying

(|-) with just two arguments. The result is a function that

still needs the final argument x.

Exercise: Think about the types involved. If

step1r has type 'a -> 'b and

step2r has type 'b -> 'c, what is the type

of step1r |- step2r?

Check: step1r |- step2r has type

'a -> 'c. (Composition “cancels” the middle type

'b.)

Now we define iterated function composition—applying a function to itself repeatedly. This is written mathematically as:

f^n(x) := \underbrace{(f \circ \cdots \circ f)}_{n \text{ times}}(x)

In other words, f^0 is the identity

function, f^1 = f, f^2 = f \circ f, and so on. In OCaml, we

first define the backward composition operator, then use it to implement

power:

let (-|) f g x = f (g x)

let rec power f n =

if n <= 0 then (fun x -> x) else f -| power f (n-1)When n <= 0, we return the identity function

fun x -> x. Otherwise, we compose f with

power f (n-1), which gives us one more application of

f. Notice how elegantly this definition expresses the

mathematical concept—we are literally composing f with

itself n times.

This power function is surprisingly versatile. For

example, we can use it to define addition in terms of the successor

function:

let add n = power ((+) 1) nHere add 5 7 would compute 7 +

1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 = 12. We could even define multiplication:

let mult k n = power ((+) k) n 0This computes 0 + k + k + \ldots + k

(adding k a total of n times), giving us k \times n. While not the most efficient

implementation, these examples show how higher-order functions like

power can express fundamental mathematical operations.

A beautiful application of power is computing

higher-order derivatives. First, let us define a numerical approximation

of the derivative using the standard finite difference formula:

let derivative dx f = fun x -> (f (x +. dx) -. f x) /. dxThis definition computes \frac{f(x + dx) -

f(x)}{dx}, which approximates f'(x) when dx is small.

Notice the explicit fun x -> ... syntax, which

emphasizes that derivative dx f is itself a function—we are

transforming a function f into its derivative function.

We can write the same definition more concisely using OCaml’s curried function syntax:

let derivative dx f x = (f (x +. dx) -. f x) /. dxBoth definitions are equivalent, but the first makes the “function returning a function” structure more explicit, while the second is more compact.

A note on OCaml’s numeric operators: OCaml uses

different operators for floating-point arithmetic than for integers. The

type of (+) is int -> int -> int, so we

cannot use + with float values. Instead,

operators followed by a dot work on float numbers:

+., -., *., and /..

This might seem inconvenient at first, but it catches type errors at

compile time and avoids the implicit conversions that cause subtle bugs

in other languages.

Now comes the payoff. With power and

derivative, we can elegantly compute higher-order

derivatives:

let pi = 4.0 *. atan 1.0

let sin''' = (power (derivative 1e-5) 3) sin

let _approx = sin''' piHere sin''' is the third derivative of sine. The

expression (power (derivative 1e-5) 3) creates a function

that applies the derivative operation three times—exactly what we need

for the third derivative.

Mathematically, the third derivative of \sin(x) is -\cos(x), so sin''' pi should

give us -\cos(\pi) = 1. The actual

result will be close to 1, with some numerical error due to the finite

difference approximation (the error compounds with each derivative we

take).

This example demonstrates the power of treating functions as

first-class values. We have built a general-purpose derivative operator

and combined it with our power function to create an nth-derivative calculator—all in just a few

lines of code.

So far, we have written OCaml programs and observed their results, but we have not precisely described how those results are computed. To understand how OCaml programs execute, we need to formalize the evaluation process. This section presents reduction semantics (also called operational semantics), which describes computation as a series of rewriting steps that transform expressions until we reach a final value.

Understanding reduction semantics is valuable for several reasons. It helps us predict what our programs will do, reason about their efficiency, and understand subtle behaviors like infinite loops and non-termination. The ideas here also form the foundation for understanding more advanced topics like type systems and program verification.

Programs consist of expressions. Here is the grammar of expressions for a simplified version of OCaml (we omit some features for clarity):

| a \; ::= | x | variables |

| \quad \mid | fun x -> a |

(defined) functions |

| \quad \mid | a \; a | applications |

| \quad \mid | C^0 | value constructors of arity 0 |

| \quad \mid | C^n(a, \ldots, a) | value constructors of arity n |

| \quad \mid | f^n | built-in values (primitives) of arity n |

| \quad \mid | let x = a in a |

name bindings (local definitions) |

| \quad \mid | match a with p -> a \mid \cdots

\mid p -> a |

pattern matching |

| p \; ::= | x | pattern variables |

| \quad \mid | (p, \ldots, p) | tuple patterns |

| \quad \mid | C^0 | variant patterns of arity 0 |

| \quad \mid | C^n(p, \ldots, p) | variant patterns of arity n |

Arity means how many arguments something requires. For constructors, arity tells us how many components the constructor holds; for functions (primitives), it tells us how many arguments they need before they can compute a result. For tuple patterns, arity is simply the length of the tuple.

Meta-syntax note. In the grammar and rules below, we

write constructors as if they were truly n-ary, e.g. C^3(a_1,a_2,a_3). In actual OCaml syntax,

constructors take exactly one argument; “multiple arguments” are

represented by a tuple, e.g. Node (v1, v2, v3). The n-ary presentation is a convenient

mathematical shorthand.

Evaluation-order note. The small-step rules below are intentionally simplified. In particular, the “context” rules allow reducing subexpressions in more than one place. Real OCaml is strict (call-by-value) and evaluates subexpressions in a deterministic order (in current OCaml implementations this is often right-to-left); the details matter when you have effects (exceptions, printing, mutation), but are usually irrelevant for purely functional code.

fix PrimitiveOur grammar above includes functions defined with fun,

but what about recursive functions defined with let rec? To

keep our semantics simple, we introduce a primitive fix

that captures the essence of recursion:

\texttt{let rec } f \; x = e_1 \texttt{ in } e_2 \equiv \texttt{let } f = \texttt{fix (fun } f \; x \texttt{ -> } e_1 \texttt{) in } e_2

The fix primitive is a fixpoint combinator. It

takes a function that expects to receive “itself” as its first argument

and produces a function that, when called, behaves as if it has access

to itself for recursive calls. This might seem mysterious now, but we

will see exactly how it works when we examine its reduction rule

below.

Expressions evaluate (i.e., compute) to values. Values are expressions that cannot be reduced further—they are the “final answers” of computation:

\begin{array}{lcll} v & := & \texttt{fun } x \texttt{ -> } a & \text{(defined) functions} \\ & | & C^n(v_1, \ldots, v_n) & \text{constructed values} \\ & | & f^n \; v_1 \; \cdots \; v_k & k < n \text{ (partially applied primitives)} \end{array}

Note that functions are values: fun x -> x + 1 is

already fully evaluated—there is nothing more to compute until the

function is applied to an argument. Similarly, constructed values like

Some 42 or (1, 2, 3) are values when all their

components are values.

Partially applied primitives like (+) 3 are also values.

The expression (+) 3 has received one argument but needs

another before it can compute a sum. Until that second argument arrives,

there is nothing more to do, so (+) 3 is a value.

The heart of evaluation is substitution. To substitute a value v for a variable x in expression a, we write a[x := v]. This notation means that every occurrence of x in a is replaced by v.

For example, if a is the expression

x + x * y and we substitute 3 for x, we get

3 + 3 * y. In our notation:

(x + x * y)[x := 3] = 3 + 3 * y.

In the presence of binders like fun x -> ... (and

pattern-bound variables), substitution must be

capture-avoiding: we are allowed to rename bound

variables so we do not accidentally change which occurrence refers to

which binder.

Implementation note: Although we describe substitution as “replacing” variables with values, the actual implementation in OCaml does not duplicate the value v in memory each time it appears. Instead, OCaml uses closures and sharing to ensure that values are stored once and referenced wherever needed. This is both more efficient and essential for handling recursive data structures.

Now we can describe how computation actually proceeds. Reduction works by finding reducible expressions called redexes (short for “reducible expressions”) and applying reduction rules that rewrite them into simpler forms. We write e_1 \rightsquigarrow e_2 to mean “expression e_1 reduces to expression e_2 in one step.”

Here are the fundamental reduction rules:

Function application (beta reduction): (\texttt{fun } x \texttt{ -> } a) \; v \rightsquigarrow a[x := v]

This is the most important rule. When we apply a function

fun x -> a to a value v, we substitute v for the parameter x throughout the function body a. This rule is traditionally called “beta

reduction” in the lambda calculus literature.

For example: (fun x -> x + 1) 5 \rightsquigarrow 5 + 1 \rightsquigarrow 6.

Let binding: \texttt{let } x = v \texttt{ in } a \rightsquigarrow a[x := v]

A let binding works similarly: once the bound expression has been

evaluated to a value v, we substitute

it into the body. Notice that let x = e in a is essentially

equivalent to (fun x -> a) e—both bind x to the result of evaluating e within the expression a.

Primitive application: f^n \; v_1 \; \cdots \; v_n \rightsquigarrow f(v_1, \ldots, v_n)

When a primitive (like + or *) receives all

the arguments it needs (determined by its arity n), it computes the result. Here f(v_1, \ldots, v_n) denotes the actual result

of the primitive operation—for example, (+) 2 3 \rightsquigarrow 5.

Pattern matching with a variable pattern: \texttt{match } v \texttt{ with } x \texttt{ -> } a \texttt{ | } \cdots \rightsquigarrow a[x := v]

A variable pattern always matches, binding the entire value to the variable.

Pattern matching with a non-matching constructor: \frac{C_1 \neq C_2}{\begin{array}{c}\texttt{match } C_1^n(v_1, \ldots, v_n) \texttt{ with } C_2^k(p_1, \ldots, p_k) \texttt{ -> } a \texttt{ | } pm \\ \rightsquigarrow \texttt{match } C_1^n(v_1, \ldots, v_n) \texttt{ with } pm\end{array}}

If the constructor in the value (C_1) does not match the constructor in the pattern (C_2), we skip this branch and try the remaining patterns (pm). This is how OCaml searches through pattern match cases from top to bottom.

Pattern matching with a matching constructor: \texttt{match } C_1^n(v_1, \ldots, v_n) \texttt{ with } C_1^n(x_1, \ldots, x_n) \texttt{ -> } a \texttt{ | } \cdots \rightsquigarrow a[x_1 := v_1; \ldots; x_n := v_n]

If the constructor matches, we substitute all the values from inside

the constructor for the corresponding pattern variables. For example,

match Some 42 with Some x -> x + 1 | None -> 0

reduces to 42 + 1 because Some matches

Some and we substitute 42 for x.

If n = 0, then C_1^n(v_1, \ldots, v_n) stands for simply

C_1^0, a constructor with no arguments

(like None or []). We omit the more complex

cases of nested pattern matching for brevity.

In these rules, we use metavariables—placeholders that can be replaced with actual expressions. Understanding them is key to applying the rules:

foo, n, or result)To apply a rule, find substitutions for these metavariables that make the left-hand side of the rule match your expression. Then the right-hand side (with the same substitutions applied) gives you the reduced expression.

For example, to apply the beta reduction rule to

(fun n -> n * 2) 5: 1. Match fun x -> a

with fun n -> n * 2, giving us x = \texttt{n} and a = \texttt{n * 2} 2. Match v with 5 3. The right-hand side

a[x := v] becomes

(n * 2)[n := 5] which equals 5 * 2

The reduction rules above only apply when the arguments are already

values. But what if we have (fun x -> x + 1) (2 + 3)?

The argument 2 + 3 is not a value, so we cannot directly

apply beta reduction. We need rules that tell us evaluation can proceed

inside subexpressions.

If a_i \rightsquigarrow a_i' (meaning a_i can take a reduction step), then:

\begin{array}{lcl} a_1 \; a_2 & \rightsquigarrow & a_1' \; a_2 \\ a_1 \; a_2 & \rightsquigarrow & a_1 \; a_2' \\ C^n(a_1, \ldots, a_i, \ldots, a_n) & \rightsquigarrow & C^n(a_1, \ldots, a_i', \ldots, a_n) \\ \texttt{let } x = a_1 \texttt{ in } a_2 & \rightsquigarrow & \texttt{let } x = a_1' \texttt{ in } a_2 \\ \texttt{match } a_1 \texttt{ with } pm & \rightsquigarrow & \texttt{match } a_1' \texttt{ with } pm \end{array}

These rules describe where reduction can happen:

let x = a1 in a2, the bound expression

a_1 must be evaluated to a value before

we can proceed. Notice there is no rule for evaluating a_2 directly—the body is only evaluated after

the substitution happens.fix RuleFinally, the rule for the fix primitive, which enables

recursion:

\texttt{fix}^2 \; v_1 \; v_2 \rightsquigarrow v_1 \; (\texttt{fix}^2 \; v_1) \; v_2

This rule is subtle but powerful. Let us unpack it:

fix is a binary primitive (arity 2), meaning it needs

two arguments before it computes.fix to two values v_1 and v_2,

it “unrolls” one level of recursion by calling v_1 with two arguments: (fix v1)

(which represents “the recursive function itself”) and v_2 (the actual argument to the recursive

call).fix has arity 2, the expression

(fix v1) is a partially applied primitive—and

partially applied primitives are values! This is crucial: it means

(fix v1) will not be evaluated further until it is applied

to another argument inside v_1.This delayed evaluation is what prevents infinite loops. If

(fix v1) were evaluated immediately, we would get an

infinite chain of expansions. Instead, evaluation only continues when

the recursive function actually makes a recursive call.

fix is not an OCaml primitive; it is a pedagogical

device. If you did want to define it directly in OCaml, you

could (ironically) do so using let rec:

let fix f =

let rec self x = f self x in

selfThe best way to understand reduction semantics is to work through examples by hand. Trace the evaluation of these expressions step by step:

Evaluate let double x = x + x in double 3

Evaluate

(fun f -> fun x -> f (f x)) (fun y -> y + 1) 0

Define the factorial function using fix and trace the

evaluation of factorial 3

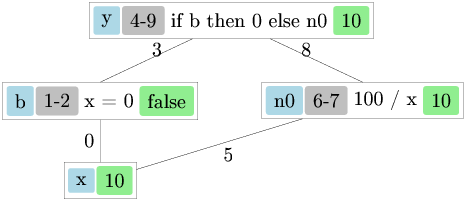

Let us see the reduction rules in action with a more substantial example. We will build a small computer algebra system that can represent mathematical expressions symbolically, evaluate them, and even compute their derivatives symbolically.

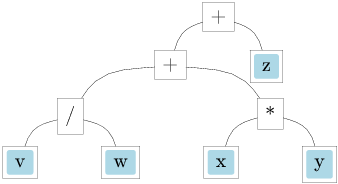

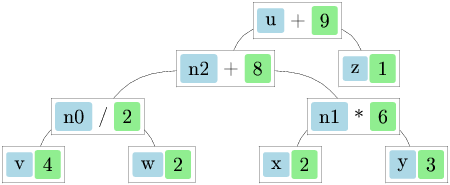

Consider the symbolic expression type from Lec3.ml:

type expression =

| Const of float

| Var of string

| Sum of expression * expression (* e1 + e2 *)

| Diff of expression * expression (* e1 - e2 *)

| Prod of expression * expression (* e1 * e2 *)

| Quot of expression * expression (* e1 / e2 *)

exception Unbound_variable of string

let rec eval env exp =

match exp with

| Const c -> c

| Var v ->

(try List.assoc v env with Not_found -> raise (Unbound_variable v))

| Sum(f, g) -> eval env f +. eval env g

| Diff(f, g) -> eval env f -. eval env g

| Prod(f, g) -> eval env f *. eval env g

| Quot(f, g) -> eval env f /. eval env gThe expression type represents mathematical expressions

as a tree structure. Each constructor corresponds to a different kind of

expression: constants, variables, and the four basic arithmetic

operations. The eval function takes an environment

env (a list of variable-value pairs) and recursively

evaluates an expression to a floating-point number.

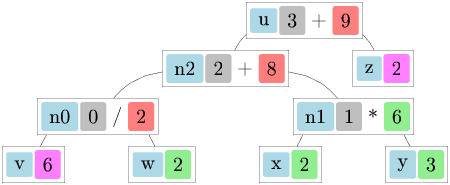

We can also define symbolic differentiation—computing the derivative of an expression without evaluating it numerically:

let rec deriv exp dv =

match exp with

| Const _ -> Const 0.0

| Var v -> if v = dv then Const 1.0 else Const 0.0

| Sum(f, g) -> Sum(deriv f dv, deriv g dv)

| Diff(f, g) -> Diff(deriv f dv, deriv g dv)

| Prod(f, g) -> Sum(Prod(f, deriv g dv), Prod(deriv f dv, g))

| Quot(f, g) -> Quot(Diff(Prod(deriv f dv, g), Prod(f, deriv g dv)),

Prod(g, g))The deriv function implements the standard rules of

calculus:

For convenience, let us define some operators and variables so we can write expressions more naturally:

let x = Var "x"

let y = Var "y"

let z = Var "z"

let (+:) f g = Sum (f, g)

let (-:) f g = Diff (f, g)

let ( *: ) f g = Prod (f, g)

let (/:) f g = Quot (f, g)

let (!:) i = Const iThese custom operators (ending in :) let us write

symbolic expressions that look almost like regular mathematical

notation.

Now let us evaluate the expression 3x + 2y + x^2 y at x = 1, y = 2:

let example = !:3.0 *: x +: !:2.0 *: y +: x *: x *: y

let env = ["x", 1.0; "y", 2.0]For nicer output, it is helpful to define a pretty-printer that

displays expressions in infix notation (this is adapted from

Lec3.ml):

let print_expr ppf exp =

let open_paren prec op_prec =

if prec > op_prec then Format.fprintf ppf "(@["

else Format.fprintf ppf "@[" in

let close_paren prec op_prec =

if prec > op_prec then Format.fprintf ppf "@])"

else Format.fprintf ppf "@]" in

let rec print prec exp =

match exp with

| Const c -> Format.fprintf ppf "%.2f" c

| Var v -> Format.fprintf ppf "%s" v

| Sum(f, g) ->

open_paren prec 0;